TMA4115: Calculus 3

Complex numbers

"A complex number is a number that can be expressed in the form

Modulus

Essentially the length of the vector from the origin to

Argument

The line from the origin to (a, b) has an angle

Polar form

Given

Multiplication

Division

Complex form

Euler's formula:

Based on that formula, we can write a complex number

Roots

When finding the

First, write

Next comes the most important step: raise both sides to the power of

Note: If you try to insert

Complex functions

Second order linear differential equations

Linear, homogenous equations with constant coefficients

Distinct real roots

Complex roots

Repeated roots

Inhomogeneous equations

The inhomogenous linear equation

In order to find

- Undetermined coefficients

- Variation of parameters

Harmonic oscillator

Step 1:

Solve the homogenous equation by solving the characteristic equation

if

if

if

Step 2:

Compute

General solution:

Vectors

A vector in this subject is always thought of as a column vector, and is written as such:

Normalization of vectors

When we normalize a vector we are making the length of the vector

Matrices

Terminology

For example, when a text says "Suppose a 4 x 7 matrix A (...)", that means that m = 4, n = 7. Can't remember the order? Rule of thumb: Just remember the word "man" and that m comes before n. m is the height of the matrix, and n is the width of the matrix.

Linear transformations

A matrix can be regarded as a transformation that transforms a vector. For example, a transformation

Onto and one-to-one

Let

$T$ is onto if and only if the columns of$A$ span$\mathbb{R}^m$ . In other words,$Ax = b$ has a solution for each$b$ in$\mathbb{R}^m$ .$T$ is one-to-one if$A$ is invertible, i.e. the columns of$A$ are linearly independent.

Inverse of a matrix

The inverse of a matrix

For example, consider the following matrix

To find the inverse of this matrix, one takes the following matrix augmented by the identity, and row reduces it as a 3 by 6 matrix:

By performing row operations, one can check that the reduced row echelon form of the this augmented matrix is:

By this point we can see that B is the inverse of A.

A matrix is invertible if, and only if, its determinant is nonzero.

LU factorization

With this technique, you can write

First, write down the augmented matrix:

Why LU factorization?

Because when

Determinants

The determinant of a 2x2 matrix is simple to compute. Here's an example:

Calculating the determinant of a larger matrix is harder. Look up "cofactor expansion" in your textbook or on the internet. Moreover, here are some useful theorems related to determinants:

-

If

$A$ is a triangular matrix, then$det\: A$ is the product of the entries on the main diagonal of$A$ . -

Adding one row of

$A$ to another row of$A$ will not change$det\: A$ . -

A square matrix

$A$ is invertible if and only if$det\: A \neq 0$ .

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors apply to square matrices.

Eigenvalue

Definition

An eigenvalue is a value that satisfies this equation:

To find the eigenvalues you evaluate the definition.

This is where

An example of finding the eigenvalues of a matrix

Given the matrix:

The roots of this polynomial are

Eigenvectors

After we have found the eigenvalues, we can find the eigenvector.

The eigenvectors are the vectors that satisfy the equation:

2D rotation matrix

Given that

The eigenvalues of

Then

Column Space and Null Space of a Matrix

The column space of a matrix A is the set Col A of all linear combinations of A. The vector

If

The rank of a matrix

The null space of a matrix A is the set Nul A of all solutions of the homogeneous equation

Basis

Col A: The pivot columns of A form a basis for the column space of A. Be careful to use the pivot columns of A itself for the basis of Col A, not the columns of an echolon form B.

Row A: The row space is not affected by elementary row operations. Therefore, the non-zero rows of the matrix in echelon form are a basis for the row space.

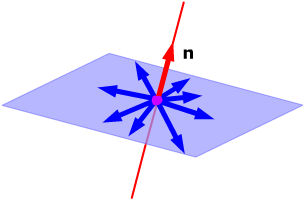

Orthogonality

A set of vectors is orthogonal if the vectors in the set are orthogonal (perpendicular) to each other. Two vectors

Orthogonal complement

The set of all vectors

Orthonormal set

An orthonormal set is orthogonal, but has one extra requirement: Every vector has length equal to 1.

If you construct a matrix

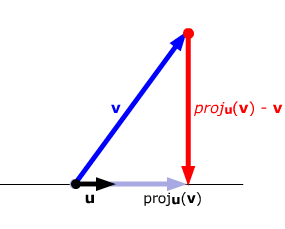

Projection

The Gram-Schmidt process

Let's say that you have a set of linearly independent vectors. The Gram-Schmidt process can orthogonalize these vectors.

Example:

QR factorization

If

You can use the Gram-Schmidt process for finding

Symmetric matrices

A symmetric matrix is a square matrix

For any symmetric matrix

If

Useful links

Recap lecture (Norwegian)

Course videos (Norwegian)

Second order differential equations on Khan Academy

Linear algebra on Khan Academy

Official website with homework assignments, old exams etc.

Differential Equations explained